The classical market for loanable funds and the zero lower bound

Here's a way explain the difference between the "classical" market for loanable funds and the "Keynesian" market for loanable funds, and bring home the important difference between market participants moving along a supply or demand curve and their moving the supply or demand curve.

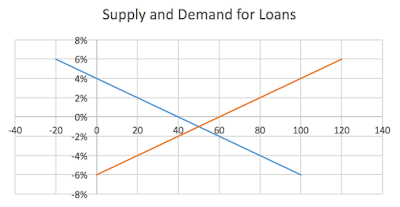

We start with a supply and demand diagram for loanable funds, with the equilibrium interest rate at 6%:

Now, consumers decide to save more, increasing the supply of loans and dropping the equilibrium interest rate from 6% to 5%:

Well done, market! Equilibrium achieved, end of story, right? Well, if all of our ceteris are paribus, yes, that's it. The market clears at 5% and our tale has ended. And that certainly could be what happens!

But it doesn't have to be what happens. Firms are manned by human actors who themselves interpret, and based on that interpretation react to, events. What if they interpret that rise in savings as an ominous sign: consumers are worried about the near future, and won't spend! Now they will reduce their demand for loans: they don't just slide along the existing demand curve; they move the demand curve:

Now our new equilibrium is 3%, not 5%! And it doesn't have to stop there: when households see that businesses are not borrowing, they believe things are even bleaker than they had imagined: they need to save more!

The equilibrium interest rate is now 1%. One more step and... businesses are now really freaking out: no one is going to buy anything next year! No sense borrowing! And... wait for it...

We have passed the zero lower bound! The equilibrium interest rate is now -1%, and can't be attained. (We have been dealing with nominal rates.) Savings now equals 60, while the desire to borrow for investment equals 40: savings exceeds intended investment. A Keynesian recession is in full bloom!

Now this, of course, is just a model. Does this happen, or does something like it happen, in the real world? That is a matter for empirical investigation. But there is nothing at all incoherent or contrary to economic logic about the story I just told. It has, as Weber would have said, explanatory adequacy, but it may or may not have causal adequacy. (Search our linked paper for those terms if you want to understand what Weber meant.)

We start with a supply and demand diagram for loanable funds, with the equilibrium interest rate at 6%:

Now, consumers decide to save more, increasing the supply of loans and dropping the equilibrium interest rate from 6% to 5%:

Well done, market! Equilibrium achieved, end of story, right? Well, if all of our ceteris are paribus, yes, that's it. The market clears at 5% and our tale has ended. And that certainly could be what happens!

But it doesn't have to be what happens. Firms are manned by human actors who themselves interpret, and based on that interpretation react to, events. What if they interpret that rise in savings as an ominous sign: consumers are worried about the near future, and won't spend! Now they will reduce their demand for loans: they don't just slide along the existing demand curve; they move the demand curve:

Now our new equilibrium is 3%, not 5%! And it doesn't have to stop there: when households see that businesses are not borrowing, they believe things are even bleaker than they had imagined: they need to save more!

The equilibrium interest rate is now 1%. One more step and... businesses are now really freaking out: no one is going to buy anything next year! No sense borrowing! And... wait for it...

We have passed the zero lower bound! The equilibrium interest rate is now -1%, and can't be attained. (We have been dealing with nominal rates.) Savings now equals 60, while the desire to borrow for investment equals 40: savings exceeds intended investment. A Keynesian recession is in full bloom!

Now this, of course, is just a model. Does this happen, or does something like it happen, in the real world? That is a matter for empirical investigation. But there is nothing at all incoherent or contrary to economic logic about the story I just told. It has, as Weber would have said, explanatory adequacy, but it may or may not have causal adequacy. (Search our linked paper for those terms if you want to understand what Weber meant.)

Comments

Post a Comment