How to Get Some Old People Alive Today to Benefit at the Expense of Some Young People Alive Today

Nick Rowe characterized Lerner's position as: "You can't make real goods and services travel back in time, out of the mouths of our grandkids and into our mouths."

And he claims this position is false.

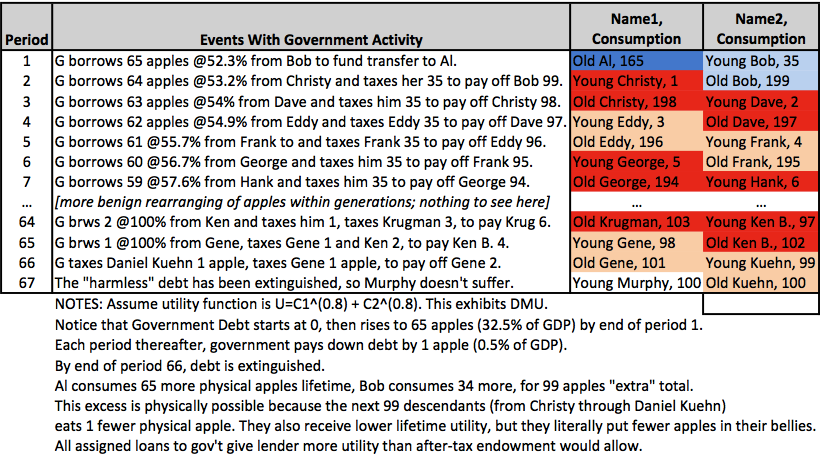

So let us look at Bob Murphy "backing" up Rowe's position. He offers the following table:

As I said, look. Look very carefully. How does Old Al benefit? He gets 65 apples from Young Bob, who is here in the present. Then Old Al dies. Therefore, every single further line of the table is utterly irrelevant to the welfare of Old Al! They have to be: he is dead. As far as Old Al goes, you can put your hand over the rest of the table. What we get is the surprising conclusion that, if we shift 65 apples of consumption from Young Bob to Old Al, Old Al is better off.

Now, Lerner clearly understood that such transfers could occur: "The real issue, and it is an important one, between the economists and Mr. Eisenhower is not whether it is possible to shift a burden (either in the present or in the future) from some people to other people..."

And what the rest of the table shows is that such transfers can keep happening in the future, as Lerner noted could happen, and they will keep having similar effects.

Now, one way to try to tie this into an anti-debt case is to note the voluntary nature of Young Bob's deal with the state: he agrees to give up 65 apples during P1 because he prefers 99 extra apples during P2. But, given that is so, Young Bob should be indifferent between that and a scheme that taxes him 65 apples during P1 and (credibly) promises to transfer 99 to him during P2. (Since either scheme at some point or other will involve taxes, a moral case against taxation is irrelevant.) I believe Steve Landsburg noted this when this debate first erupted, what, five decades ago? So I still believe my conclusion is sound: The effect on Old Al can be analyzed entirely in terms of period 1. He benefits from a direct transfer. Whether that is done by debt or taxation is entirely irrelevant to Old Al's gain. And, most importantly, given the irrelevance of the rest of the table to Old Al's situation, he did not benefit from any of those later transfers at all. He was, after all, pushing up daisies. Six feet under. Expired and gone to meet his maker. He is a late entitlement gatherer. A stiff. Bereft of life. Old Al is an ex-tax-recipient.

Now, the intuition that I think is driving the use of this model is "But look: If Young Bob didn't think he could get his apples back plus more, the thing couldn't get rolling. And he has to convince Christy of the same!" Well, of course Ponzi schemes are (by definition) unsustainable, and of course if this debt financing has been sold to citizens as a Ponzi scheme, there will be trouble down the road. (If the economy grows faster than the debt re-payments, per Samuelson, then the debt financing is not a Ponzi scheme at all, or, perhaps, per Rowe, is a "sustainable Ponzi scheme.") But as we well know, Ponzi schemes don't essentially rely on explicit debt contracts! It is the constant, growing transfers from investor generation N + 1 to investor generation N that characterizes a Ponzi scheme. So, once again, I conclude it is not the debt that is at issue in these OLG models, it is the inter-generational transfers.

And I conclude that Lerner's basic point was sound. In the entire table above, no real goods and services travelled back in time. Of course, Lerner understood that right this moment, I can eat my kid's desert. And next generation, my kid might do the same to his kid. And so on. And we don't need debt to make that happen!

So let us look at Bob Murphy "backing" up Rowe's position. He offers the following table:

As I said, look. Look very carefully. How does Old Al benefit? He gets 65 apples from Young Bob, who is here in the present. Then Old Al dies. Therefore, every single further line of the table is utterly irrelevant to the welfare of Old Al! They have to be: he is dead. As far as Old Al goes, you can put your hand over the rest of the table. What we get is the surprising conclusion that, if we shift 65 apples of consumption from Young Bob to Old Al, Old Al is better off.

Now, Lerner clearly understood that such transfers could occur: "The real issue, and it is an important one, between the economists and Mr. Eisenhower is not whether it is possible to shift a burden (either in the present or in the future) from some people to other people..."

And what the rest of the table shows is that such transfers can keep happening in the future, as Lerner noted could happen, and they will keep having similar effects.

Now, one way to try to tie this into an anti-debt case is to note the voluntary nature of Young Bob's deal with the state: he agrees to give up 65 apples during P1 because he prefers 99 extra apples during P2. But, given that is so, Young Bob should be indifferent between that and a scheme that taxes him 65 apples during P1 and (credibly) promises to transfer 99 to him during P2. (Since either scheme at some point or other will involve taxes, a moral case against taxation is irrelevant.) I believe Steve Landsburg noted this when this debate first erupted, what, five decades ago? So I still believe my conclusion is sound: The effect on Old Al can be analyzed entirely in terms of period 1. He benefits from a direct transfer. Whether that is done by debt or taxation is entirely irrelevant to Old Al's gain. And, most importantly, given the irrelevance of the rest of the table to Old Al's situation, he did not benefit from any of those later transfers at all. He was, after all, pushing up daisies. Six feet under. Expired and gone to meet his maker. He is a late entitlement gatherer. A stiff. Bereft of life. Old Al is an ex-tax-recipient.

Now, the intuition that I think is driving the use of this model is "But look: If Young Bob didn't think he could get his apples back plus more, the thing couldn't get rolling. And he has to convince Christy of the same!" Well, of course Ponzi schemes are (by definition) unsustainable, and of course if this debt financing has been sold to citizens as a Ponzi scheme, there will be trouble down the road. (If the economy grows faster than the debt re-payments, per Samuelson, then the debt financing is not a Ponzi scheme at all, or, perhaps, per Rowe, is a "sustainable Ponzi scheme.") But as we well know, Ponzi schemes don't essentially rely on explicit debt contracts! It is the constant, growing transfers from investor generation N + 1 to investor generation N that characterizes a Ponzi scheme. So, once again, I conclude it is not the debt that is at issue in these OLG models, it is the inter-generational transfers.

And I conclude that Lerner's basic point was sound. In the entire table above, no real goods and services travelled back in time. Of course, Lerner understood that right this moment, I can eat my kid's desert. And next generation, my kid might do the same to his kid. And so on. And we don't need debt to make that happen!

Gene,

ReplyDeleteIf Eisenhower or Brooks had proposed setting up a tax and transfer Ponzi scheme to finance current spending instead of using debt, then this would be a good objection. But they weren't. I'm sure if you went up to Brooks or Ike and proposed instituting a Ponzi scheme they would have been horrified. So why can't they be equally horrified when we do the same thing using debt?

The question is, is issuing government debt *essentially* a Ponzi scheme? No, it isn't.

DeleteCould a Ponzi scheme *happen* to employ government debt in its execution?

Yes, it could. But what we should object to is the Ponzi scheme.

To do otherwise is like saying, "Hmm, common stock has sometimes been used in Ponzi schemes. Therefore, I condemn common stock!"

Or turn your question around, blackadder: Do you seriously think Lerner was proposing, "Hey: Let's issue a bunch of debt, and turn the money over exclusively to old folks for consumption, while selling the bonds exclusively to youngsters. We'll tell the youngsters this is cool, because when they are old, we devise a tax that falls exclusively on the then young to make it up to them"?

DeleteSo: "So why can't they be equally horrified when we do the same thing using debt?"

Because no one was proposing doing that using debt.

The question is, is issuing government debt *essentially* a Ponzi scheme?

ReplyDeleteI don't think either Eisenhower or Brooks was making such a broad point. They didn't claim that all debt burdens the children of the people who incur it. Clearly it doesn't. They were saying that some particular debt was going to burden our children. You can't refute that claim by pointing out that debt doesn't always burden our children.

Or turn your question around, blackadder: Do you seriously think Lerner was proposing, "Hey: Let's issue a bunch of debt, and turn the money over exclusively to old folks for consumption, while selling the bonds exclusively to youngsters. We'll tell the youngsters this is cool, because when they are old, we devise a tax that falls exclusively on the then young to make it up to them"?

I don't think Lerner was making this sort of argument. Lerner's argument was about the ordinary English meaning of the phrase "future generations," which, as I've explained previously, I think is flawed.

Gene Callahan,

ReplyDeleteYou wrote:

"Now, one way to try to tie this into an anti-debt case is to note the voluntary nature of Young Bob's deal with the state: he agrees to give up 65 apples during P1 because he prefers 99 extra apples during P2. But, given that is so, Young Bob should be indifferent between that and a scheme that taxes him 65 apples during P1 and (credibly) promises to transfer 99 to him during P2. (Since either scheme at some point or other will involve taxes, a moral case against taxation is irrelevant.)"

One cannot be indifferent between a voluntary payment and an involuntary one. By definition, involuntary payment of $100 (taxation) is ranked lower on one's value scale than all voluntary payments of $100 (e.g. lending to a borrower), which is precisely why coercion is necessary in taxation to get people, all people, to pay the $100.

You're not making any sense by invoking a scenario where a person is indifferent between choosing one payment stream that is voluntary, and another equal payment stream but is involuntary. By definition, a person CANNOT be indifferent between a voluntary and an involuntary action.

Moreover, the whole notion of a "tax 65 apples now and promise to pay back 99 apples later" doesn't mean what you think it means. This is nothing but an involuntary debt contract. Just because the numbers are the same, it doesn't entitle you to say that the person should be indifferent.

There are many other examples where the premise in your argument can be seen as flawed:

1. A person should be indifferent between working under the threat of death for $20 an hour, and working the same job voluntarily for $20 an hour.

2. A person should be indifferent between giving their gold watch to charity, and having someone rob them of their watch after which it is given to the same charity.

3. A person should be indifferent between having their car involuntarily taken from them for a thug's weekend joy ride, and voluntarily permitting that thug to drive the car over the weekend.

In all these examples, the goods, the things, in question, are all equal in terms of their "movements", but clearly they are vastly different when the individual's valuations are taken into account!

The error you are making is that you are abstracting away from individual utility, individual action, and you are focusing only on the mechanical, sterile movements of the goods themselves. You can't do that when the subject is economics.

Pete Petepete (may I call you Repeat?),

DeleteYou are being very silly. The whole point is that, in this case, Young Bob would *voluntarily* agree to the tax-and-transfer scheme, given he would voluntarily but the bond.

Taxes are only involuntary if you don't wanna pay them!

Gene Callahan,

ReplyDeleteYou wrote:

"So I still believe my conclusion is sound: The effect on Old Al can be analyzed entirely in terms of period 1. He benefits from a direct transfer. Whether that is done by debt or taxation is entirely irrelevant to Old Al's gain. And, most importantly, given the irrelevance of the rest of the table to Old Al's situation, he did not benefit from any of those later transfers at all. He was, after all, pushing up daisies."

The OLG model doesn't just analyze the effect of debt on the first generation (Old Al). The 65 apples that Young Bob lent to the government, which then went to Old Al, is not paid back all in the first generation. It is amortized over subsequent generations, via taxes. It is therefore a confusion to claim that you have nullified the OLG model by making a point about the effect on Old Al only.

"Now, the intuition that I think is driving the use of this model is "But look: If Young Bob didn't think he could get his apples back plus more, the thing couldn't get rolling. And he has to convince Christy of the same!" Well, of course Ponzi schemes are (by definition) unsustainable, and of course if this debt financing has been sold to citizens as a Ponzi scheme, there will be trouble down the road. (If the economy grows faster than the debt re-payments, per Samuelson, then the debt financing is not a Ponzi scheme at all, or, perhaps, per Rowe, is a "sustainable Ponzi scheme.") But as we well know, Ponzi schemes don't essentially rely on explicit debt contracts! It is the constant, growing transfers from investor generation N + 1 to investor generation N that characterizes a Ponzi scheme. So, once again, I conclude it is not the debt that is at issue in these OLG models, it is the inter-generational transfers."

So if I invested in a financial security that can be synthetically replicated by longing and shorting a set of other financial securities, then I cannot claim that the actual security I invested in is the cause for my profit or loss? I have to agree with you if you said that it's not the financial security I invested in per se that garnered me a profit or loss, because you can find a way to replicate the payments schemes via a synthetic portfolio?

All you're doing is denying the causal force of the financial security I invested in, and by construction, all your doing is denying the causal force of the debt as the engine of the OLG model.

It is no argument against ANY argument to say that because you can replicate the mechanical motions of tangible objects via some other method than the one concerned, that the one concerned didn't happen.

Your epistemology is flawed.

Repeat,

Delete"a confusion to claim that you have nullified the OLG model"

If I had claimed that your argument might have some merit!

As for the rest of your post: no. It is like this: I have invested in a security while wearing a bandana. I note that I could have not been wearing the bandana and gotten the same results. You say, "Hey that doesn't negate the causal effects of the bandana.

And so far as epistemology goes, you shouldn't use big words whose meanings are unfamiliar to you.

"It is no argument against ANY argument to say that because you can replicate the mechanical motions of tangible objects via some other method than the one concerned, that the one concerned didn't happen."

DeleteOh, and this is the stupidest paragraph I have seen in the comments in months!